对称作为美学原则

对称作为一种美学原则。因为帕拉第奥对称是和谐的必要条件。他把它作为一个绝对的规则,从不偏离它。在轴对称中,人们避免用固体元素占据中心。古代的庙宇和宫殿,除了米诺斯人,总是有一个偶数的柱子,所以中间是一个中间入口。从埃及到文艺复兴,直到18世纪,双边或中心对称基本上是为宗教建筑和那些寻求象征世俗权力的建筑保留的。从19世纪开始,对称被越来越多地用于各种普通建筑、小型住宅、公寓楼、工厂、屠宰场、变压器等。随着对称性的普及,它已经失去了作为例外的价值,因此也就失去了它集体象征意义的一部分。这种贬值的一个后果是,20世纪的建筑可以通过不对称来达到权威或宗教的象征( 日内瓦国际联盟竞赛,勒·柯布西耶,1927年 )。当然,这并不是新空间概念出现的唯一原因,但轴对称的过度使用可能间接地造成了它暂时的声名狼藉。

Symmetry as an aesthetic principle. For Palladio symmetry is a sine qua non of harmony. He sets it up as an absolute rule and never departs from it. In axial symmetry one avoids occupying the centre with a solid element. The temples and palaces of antiquity, except the Minoan, always have a front with an even number of columns so that the middle is an interval-entrance. From Egypt to the Renaissance and until the eighteenth century, bilateral or central symmetry is reserved essentially for religious buildings and for those which seek to symbolize secular power. From the nineteenth century symmetry is used more and more for all sorts of ordinary buildings, small residential houses, blocks of flats, factories, slaughterhouses, transformers, etc. By its popularization, symmetry has lost its value as an exception and, consequently, part of its collective symbolic significance. One consequence of this devaluation is that the twentieth century can just as well resort to asymmetry as to symmetry to achieve buildings representative of authority or religion (Figure 94). Certainly this is not the only reason why new spatial concepts have appeared, but the over-use of axial symmetry has probably played an indirect role in its temporary disrepute.

对称作为建造的原则

对称作为一个建设性的原则。对 维奥莱·勒·迪克 来说,棱纹拱顶具有对称性。我们必须强调这条思想路线的合理性,以及它在简支梁、框架、拱顶、圆顶等静力学定律中的基础。但是,如果合理的结构要求跨度和荷载的对称,它就不会对一组跨度施加等级对称。此外,现代的施工方法,特别是混凝土的连续性和改变其加固的可能性,允许我们在场地条件、内容或审美意图证明其合理性时,合理地利用结构不对称。

Symmetry as a constructive principle. For Viollet-le-Duc it is the ribbed vault which engenders symmetry. One must stress the rational- ity of this line of thought and its basis in the laws of statics for simple spans, frames, vaults, domes, etc. But if rational construction requires symmetry of the span and loading, it does not impose a hierarchical symmetry on a group of spans. Moreover, modern methods of construction, notably the continuity of concrete and the possibility of varying its reinforcement, allow us to make rational use of structural asymmetry when the conditions of site, content or aesthetic intention justify it.

对称是规则还是禁忌

对称具有一种完美平衡的特质,但它常常会引起一种奇怪的不安,即使在大师的作品中也是如此。令人不安的不是这种对称性本身,而是它的轴向走向,这往往是一种必然的结果。走钢索是不可能的;它会导致不平衡。也许正是这种建筑对人类的羞辱让我们拒绝它,尤其是当它与“法西斯”建筑的巨大规模联系在一起的时候。然而,只有思想和思想才是法西斯。没有“法西斯主义”建筑,就像没有“民主主义”、“保皇主义”或“马克思主义”建筑一样。不朽不只是一种社会形式的特权。

Symmetry has a quality of perfect balance but it often provokes a strange uneasiness, even in the works of great masters. What is disturbing is not the symmetry in itself, but rather its axial approach, which is all too often a corollary. To walk along the tightrope of an axis is impossible; it causes imbalance. It is perhaps this humiliation of man by architecture which makes us reject it, especially if it is linked to the colossal scale of ‘fascist’ architecture. However, only thoughts and ideas are fascist. There is no ‘fascist’ architecture in the same way as there is no ‘democratic’, ‘royalist’ or ‘Marxist’ architecture. Monumentality is not the prerogative of just one form of society.

这是不是说所有关于对称的观点都必须被摒弃?一点也不:对称仍然为我们的眼睛提供了一种平衡的满足感,以及轻松创造一个从环境中脱颖而出的统一的力量。但在今天,美感肯定不再像文艺复兴时期那样依赖于对称性,而文艺复兴时期正是对对称性的推崇。相反,二十世纪的人已经学会了欣赏平衡的不对称和对既定秩序的微妙偏离,不管它们是否对称。我们欣赏不对称和对称的物体。

Is this to say that every idea of symmetry must be rejected? Not at all: symmetry still offers our eye a satisfaction of balance and the power to create with ease a unity standing out from the rest of the environment. But today the sensation of beauty is certainly no longer dependent on symmetry as in the period of the Renaissance which canonized it. On the contrary, the twentieth-century eye has learnt to appreciate balanced asymmetries and subtle deviations from an established order whether they be symmetrical or not. We appreciate both asymmetric and symmetric objects.

我们可以把人的脸和外表作类比。如果这个物体是对称的,从一个斜角而不是从前面“平淡”地看它,不是更感性吗?我们会看着对方的眼睛,但我们很少直视对方,也不会看太久。坚持创造了不安。报纸只刊登警察追捕的罪犯的全貌,从不刊登诗人或演员的全貌!另一方面,建筑杂志上刊登了对称建筑的“正面全貌”照片,这可能是为了将它们与建筑师习惯使用的立面图进行比较。这常常忽略了被拍摄对象的真实感知。使用轴向方法处理对称性是一件很微妙的事情。轴线不是用于日常生活,而是用于仪式。

Analogies can be made between the human face and a façade. If the object is symmetrical, is it not more sensual to see it from an oblique angle rather than ‘prosaically’ from the front? We look into the eyes of the person to whom we are talking, but we rarely look straight at him, and never for long. Insistence creates uneasiness. Newspapers only show full-face views of criminals sought by the police, never poets or actors! Architectural magazines, on the other hand, contain photographs of ‘full-frontal’ views of symmetrical buildings, possibly in order to compare them with the elevational drawing to which architects are accustomed. This often misses the real perception of the photographed object. Symmetry is a delicate thing to handle with an axial approach. The axis is not for the everyday, it is reserved for ceremony.

为了说明在这一领域建立规则是多么困难,我将举一个来自文艺复兴时期的例子。在这个伟大的建筑时期,有许多杰出的作品产生了完美的对称,但同时也否定了轴线的重叠和人们通过整体所走的路线。在罗马广场del Campidoglio由米开朗基罗设计在16世纪(图96),大台阶导致广场实际上是位于轴,但地形,仍然相当大距离的步骤,及其伟大的宽度给它一定的自主权。这一系列的步骤是必要的,以准备和宣布的作用和特殊的情况下,卡皮托里诺宫在城市结构。一旦到达广场,一切都被安排好,行人的路线远离轴线:在角落里有四个其他的入口,正门在正中间,但是通向它的台阶是从角落里升起的。广场的中央被一个“理念”(马可·奥勒留的骑术雕像)占据,地面的纹理是如此的有力度和细节,它获得了一定的自主性,同时仍然尊重它与轴线的关系。

In order to show how difficult it is to establish rules in this field, I shall take an example which comes from the Renaissance. In this great architectural period, there are remarkable works which produce perfect symmetry, but at the same time they deny the superimposition of the axis and the route one takes through the ensemble. In the Piazza del Campidoglio designed by Michelangelo in Rome in the sixteenth century (Figure 96), the grand flight of steps which leads to the square is in fact situated on the axis, but the topography, the still considerable distance from the steps to the building, and its great width give it a certain autonomy. This flight of steps is necessary to prepare and proclaim the role and particular situation of the Palazzo Capitolino in the urban fabric. As soon as one reaches the square, everything is arranged so that the pedestrian’s route moves away from the axis: there are four other accesses in the corners, the main door is right in the middle, but the steps which lead to it rise from the corners. The middle of the square is occupied by an ‘idea’ (the equestrian statue of Marcus Aurelius) and the texture of the ground has been achieved with such strength and detail that it gains a certain autonomy relative to the building while still respecting its relationship to the axis.

在二十世纪的建筑中,对称有时是规则,但更多时候是禁忌。对于里特维尔德、格罗皮乌斯和勒柯布西耶来说,这可以在他们的早期作品中找到。对于密斯·凡·德·罗、阿斯普伦德和后来的卡恩来说,这是构成的基本原则,尤其是在他们后期的作品中。从20世纪20年代的包豪斯建筑开始,一直到20世纪六七十年代,现代建筑学派都倾向于反对它,甚至把它作为一种美学原则加以压制,而它的建筑价值却从未受到质疑。他们一方面提到了造型艺术的发展,另一方面也提到了一种倾向,即建筑形式以场地的诗意和实用需求为出发点,而不是简单的几何秩序的抽象。今天,这些学校承认这两种组织形式,但不把优越性加诸于其中一种,也不解释增加成功机会的因素。

In twentieth-century architecture, symmetry has sometimes been the rule, but more often taboo. For Rietveld, Gropius and Le Corbusier it can be found in their early works. For Mies van der Rohe, Asplund and later Kahn it was an essential principle of composition, especially in their later works. Schools of modern architecture since the 1920s with the Bauhaus, and up to the 1960s or 1970s, have tended to advise against it, even repressed it, as an aesthetic principle, whilst its constructional value was never doubted. They referred, on one hand, to the development of the plastic arts, and on the other to a tendency for architectural form to take as its starting point the poetic and utilitarian demands of the site rather than the abstraction of a simple geometric order. Today these same schools admit both forms of organization without attributing superiority to one or the other, but also without explaining the factors which increase their chances of success.

对称不一定是完美的

对称不一定是完美的。人类的脸很少是完全对称的。对对称的次要偏离并不影响建筑整体的总体印象;他们甚至可以软化它的僵硬。

Symmetry does not have to be perfect. The human face is rarely completely symmetrical. Secondary departures from symmetry do not affect the general impression of an architectural whole; they can even soften its starkness.

不对称的平衡

我们已经看到,在维特鲁威时代,在古代,在中世纪,在文艺复兴时期,一直到十九世纪,如果不借助于中轴或中心对称,就不可能想象出建筑的平衡和不朽的尊严。直到现在,不对称的平衡一直是绘画和雕塑的保留,就建筑设计的有意识意图而言,它是20世纪西方的主要收获之一(图103)。早期的应用在欧洲相当罕见。然而,有英国的风景传统,但在这里,它的组成似乎,实际上,是由于绘画,它作为一个模型使用。

We have seen that in the time of Vitruvius and in Antiquity, to which he refers, in the Middle Ages, in the Renaissance and up to the nineteenth century, it was impossible to conceive of balance and the monumental dignity of architecture without recourse to axial or central symmetry. Having been the preserve until now of painting and sculpture, asymmetrical balance is, in so far as it is a conscious intention of an architectural design, one of the main Western acquisitions of the twentieth century (Figure 103). Earlier applications of note are rather rare in Europe. There is, however, the English landscape tradition, but here it would seem, in fact, that its composition owes something to painting, which it used as a model.

不对称平衡的基本规则比对称的规则更难理解和传达。水平和垂直起着至关重要的作用。我们的直立位置,顶部和底部,水平或垂直线,两者之间的直角,立即被理解,我们能够辨别出最轻微的偏差。这些现象比比例现象更容易精确地理解。

The underlying rules of asymmetrical balance are more difficult to understand and convey than those of symmetry. The horizontal and vertical play essential roles. Our upright position, top and bottom, horizontal or vertical line, the right-angle between the two, are immediately understood and we are able to discern the slightest deviations. These phenomena are easier to perceive with precision than are proportions.

另一方面,我们发现的整个世界,从婴儿期到成年期,都与重力的体验有关。从更广泛的意义上说,我们每天都在利用杠杆的不对称原理:打开一个罐头,拔出一颗钉子,移动一个重物。

On the other hand the whole of our discovery of the world, from infancy to adulthood, is linked to the experience of gravity. In a wider sense we make daily use of the asymmetrical principle of leverage: to open a tin, pull out a nail, move a weight.

在一个立面上,尤其是在一个剖面上,万有引力的原理立即介入,因为我们很清楚所有建筑物都试图抗拒的地球引力。通过Robert Maillart设计的桥或带肋拱顶传递到地面的力的通量,提供了各部分作用和反应的直接图像(图107)。这些类型的建筑唤起我们对自然之美、精确和平衡的意识。在更高的抽象层次上,我们在平面或空间上的所有物体组合中都能感知到一种平衡或不平衡的状态。让我们以立面上的窗户为例。墙,首先是保证静态平衡的建筑实体,在我们的感知中起着次要的作用。它成为一个游戏的背景和框架,在这个游戏中,假想的重量和平衡(开口)之间的紧张关系是平衡的。水平、垂直和重力的原则在我们心中根深蒂固,它们继续产生影响。这就是Paul Klee谈论不对称平衡的原因(图108)。

In a façade, and above all in a section, the principle of gravity intervenes immediately, since we are well aware of the forces of terrestrial attraction which all buildings try to defy. The flux of forces expressed, transmitted to the ground by a bridge by Robert Maillart, or by a ribbed vault, provide an immediate image of the action and reaction of the parts (Figure 107). These types of construction arouse in us an awareness of the beauty, precision and balance of nature. At a higher level of abstraction, we perceive a state of equilibrium or disequilibrium in all groupings of objects on a plan or in space. Let us take the example of windows in a façade. The wall, which is first of all a constructional reality to guarantee static balance, adopts a secondary role in our perception. It becomes background and framework for a game of imaginary weights and counterbalances (the openings) between which tensions are to be balanced. The principles of horizontal, vertical and gravity are so deep-rooted in us that they continue to exert an influence. That is what led Paul Klee73 to talk about asymmetrical balance (Figure 108).

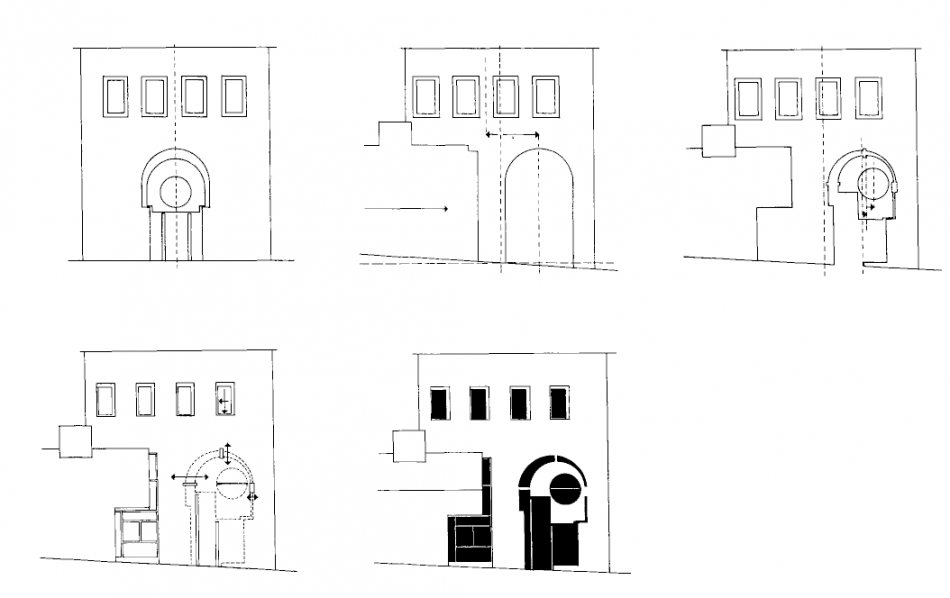

鲁道夫·阿恩海姆(Rudolf Arnheim)在其作品《艺术与视觉感知》(Art and Visual Perception)中以“平衡”为题分析了这一现象。’34最近几乎没有任何作品增加了我们对视觉平衡现象的了解。至少在目前,我们将通过反复试验来进行。然而,对一些原则的了解可以加速这一进程。我们通过检查一个要改造的立面来展示如何通过特定的干预来恢复它的平衡(图109和110)。

Rudolf Arnheim analyses this phenomenon under the title ‘balance’ in his work ‘Art and Visual Perception.’34 There are hardly any recent works which have increased our knowledge of the phenomena of visual balance. At least for the moment, we will proceed by trial and error. Knowledge of a few principles can nevertheless accelerate this process. We present an example of it by examining a façade to be transformed in order to show how certain interventions can restore its balance (Figures 109 and 110).

Atelier Cube (G. and M.Collomb, P. Vogel)

平衡现象在水平面上或空间上也起作用。精心摆放在桌子上的物品,艺术家的静物画,或广场周围的建筑物,都创造了一种平衡或不平衡的紧张关系,就像我们刚才概述的那样。科林·罗(Colin Rowe)的城市设计是最出色的平衡展示。

平衡的反面不是动态,而是不平衡、不稳定、不确定、混乱。弗兰克·劳埃德·赖特的房子并不是不平衡的,但它们强调了进场路线和场地的主要方向。当作用力之间的距离没有通过适当的“平衡”来精确平衡时,就会产生不平衡;记住杠杆臂的图像。

The phenomena of balance also come into play on a horizontal plane or in space. Objects carefully set out on a table, an artist’s still life, or the buildings around a square create relationships of balanced or unbalanced tensions similar to those we have just outlined. Colin Rowe’s urban designs are most remarkable demonstrations of balance.

The opposite of balance is not dynamism, but imbalance, instability, uncertainty, confusion. Frank Lloyd Wright’s houses are not unbalanced, but they emphasize the approach route and the principal directions of the site. Imbalance results where the distances between the acting forces have not been accurately balanced by the play of appropriate ‘counterbalances’; remember the image of the lever arm.

[…] 4.3 平衡(对称、不对称平衡) […]