原文:El Croquis 191 Go Hasegawa,A Conversation with Go Hasegawa:ARCHETYPES AND PROTOTYPES

你继续在冢本由晴的指导下获得了博士学位?

是的,我在2015年拿到了博士学位。我的博士论文有三篇。我在硕士学位期间就已经和冢本由晴合作写过一篇。但是在我工作了十年之后,我觉得有必要完成博士学位。工作有时会使视野会变得太狭窄。我需要对建筑有一个更长远的展望。

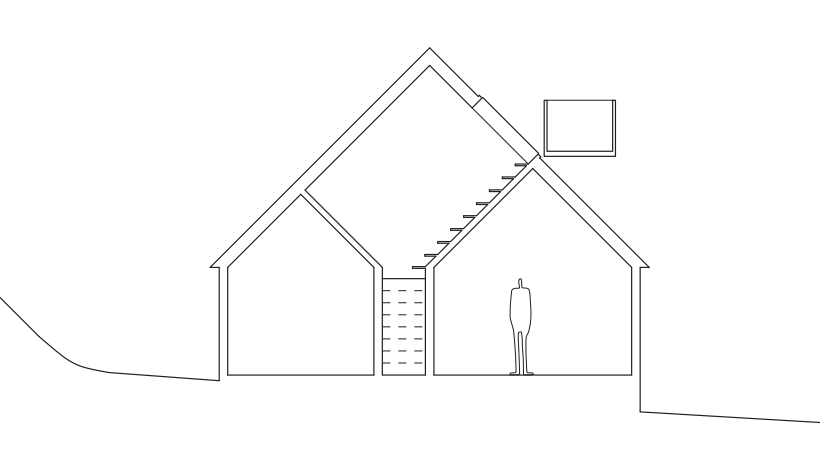

你的博士论文似乎更接近于筱原一男的研究,而不是冢本由晴或坂本一成的,因为它关注的是小建筑的比例问题。冢本由晴或坂本一成关注的首要问题是环境,而筱原一男则更深入地研究了身体和空间的关系。例如,你关于比例研究展开的建筑形式调查,这就把“行为学”的知识放在了一边。你的建筑,森之宅(House in a Forest ),甚至最近的瓜斯塔拉教堂(Chapel in Guastalla),它们精确的几何形状和清晰的空间划分,似乎更能让人联想起筱原一男,而不是你的老师。

事实上,我一直在通过我的工作研究建筑的形式问题。在这个意义上,我认同与筱原一男的比较。但坂本一成的做法在一定程度上也是如此。例如,代田集合住宅项目(Townhouse in Daita),在不同内部空间的衔接中,对比例表现出了一种难以置信的敏感性。正是在这个项目里,我理解了“相对比例”的概念。虽然我自己的作品可能以单纯的形式和空间为特征,但它也处理了特定情况下比例的意义,而不太关注绝对值。

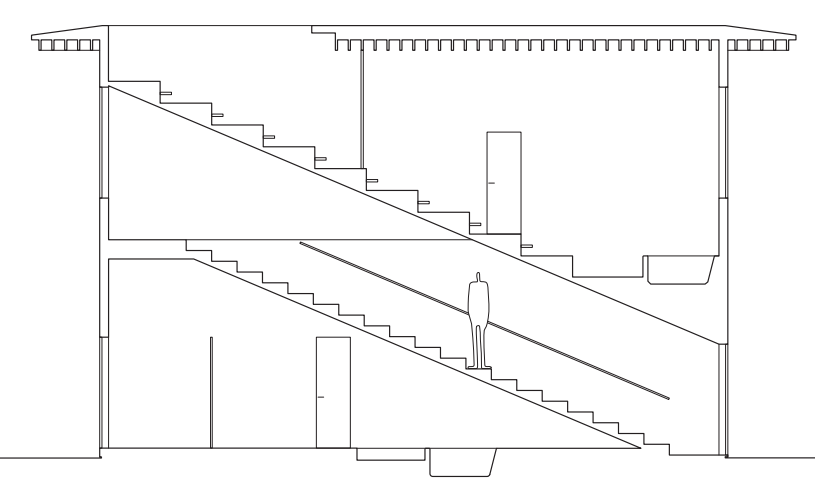

我想说我读博士的目的不是为了完成学位,而是为了更好地理解我自己的工作,明确我的方法,尤其是建筑的比例。在筱原一男的理论中,比例意味着由特定比例体系所带来的美,具有理想主义色彩。初等几何或对称性几乎是它的前提。然而,我的目标是把使用者和他们的身体感知作为我调查的核心,比例不是绝对的,而是一种关系。这种转变可以追溯到20世纪90年代的一系列建筑中,我通过研究不同大小的房间、不同层高、不同要素之间的关系来研究这些建筑。将比例作为一组关系的理解具有真正的潜力。比如说,在我设计的森林空中别墅(Pilotis in a Forest)里,森林中的架空柱子就很重要。如果他们再低一点,房子的建筑属性就会过强。如果它们再高一点,房子就会变成一个融入森林的树屋了。从环境中寻找相对比例的可能性,是我的研究和实践的一个基点。

建筑要素似乎在你的建筑中扮演着重要的角色。你经常会把它们称为整个项目的关键:森林空中别墅(Pilotis in a Forest)的“架空柱”,练马公寓(Nerima Apartments)的“阳台”,以及上尾住宅(Rowhouse in Ageo)的“窗户”。

每个人都知道屋顶或阳台是什么,而这一点让我可以很容易地与非建筑师讨论项目。但这一点同时也可以超越了日常交流的范畴。建筑要素也允许与环境互动,这就是我在设计时所寻找的关键:相似性,而不是独特性。

在一篇关于日本屋顶的文章中,你提出了一个日本的原型,其中屋顶是处于支配的地位,而墙被认为是次要的要素。这些元素是一个更深刻的或甚至历史范式的一部分吗?你是否同时在寻找原型和范式?

我认为两者都有。建筑要素的可能性和组合方式都是无限的。在每一栋建筑里,你都可以重新定义它们。但是正如我之前提到的,场地的文脉在我的设计中扮演了重要的角色。我在轻井泽的第一个建筑,森之宅(House in a Forest),和其他建筑一样,有着陡峭的屋顶。蒲江宅(House in Kamae)重新诠释了社区中常见的前花园。浅草的联排别墅(Townhouse in Asakusa)则以阳台为主题。但与此同时,我总是关心一个普世性的表达。因此,对于我来说,普世性和独特性并不矛盾。我在每个特定的项目中寻找普世性的东西。

你在实践中是如何转译这些的呢?

用比例的概念来表述它的可能是最合适的,它既涉及形式和环境,也涉及空间和尺度,以及它们与身体的关系,还涉及特定的位置、特定的地形、气候、时间等。我深信有必要以具体的方式处理一个项目的具体情况。业主决定了每个项目的不同。尽管许多建筑师是并不关心这些问题,但我认为这是一个与建筑环境同质化作斗争的机会。每个人都以不同的方式生活,塑造了不同的空间。因此,我想知道我的业主是如何生活的,他们拥有什么样的物品,他们在家里如何活动的,他们是如何打扫他们的房子。这就是我的设计开始的地方。事实上,当设计一个项目,我会约在他们的家里见面,即使我需要携带巨大的模型过去。

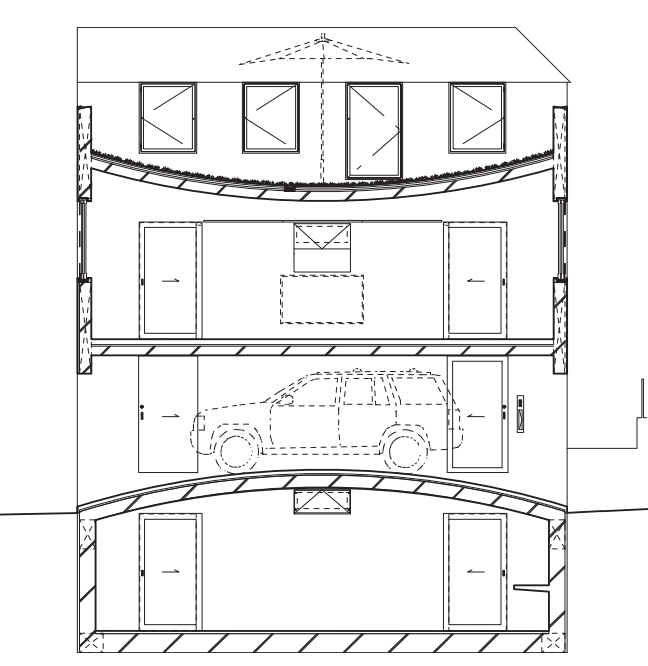

例如,在三轩茶屋宅(House in Sangenjaya)中,工作繁忙的业主希望拥有一个像花园一样的户外空间,在周日可以在那里放松几个小时。这成为了设计的突破点。在涩谷附近一个非常密集的城区,我发现每个房子和公寓都有一个非常小的阳台。我只是颠倒了房子和阳台的比例:在顶层,房子只有1.1米宽,但有一个2.6米宽的凹阳台。同样,在一楼,业主需要一个非常大的有顶的停车场来停放他们的吉普车。因此,我们提供了一个相应的凹形入口通道,同时允许一些光线进入地下室的卧室。

You also did a PhD under Tsukamoto’s supervision.

Yes, I received it in 2015. My PhD consists of three papers. I had already written one during my master’s degree, in collaboration with Tsukamoto. But after working for ten years in my office, I felt the need to finish the PhD. The work in the office can become too focused sometimes. I needed a somehow more distant view on architecture.

Your PhD seems more related to Shinohara’s formal research than to Tsukamoto’s or Sakamoto’s, as it pursues the question of proportion in small buildings. Tsukamoto’s and Sakamoto’s research is at first concerned with the concept of environment, whereas Shinohara’s more closely investigated the relation between body and space. Your research on proportion participates in a formal investigation of architecture, which leaves the knowledge about ‘behaviorology’, for instance, aside. Your buildings, House in a Forest or even the recent Chapel in Guastalla, with their very precise geometrical and spatial clarity, seem to resonate more with Shinohara’s interest than with those of your teachers.

Indeed, I have been investigating through my work and research the formal properties of architecture. In this sense, I could agree with the comparison with Shinohara. But the same is true to a certain degree for Sakamoto’s practice. The Townhouse in Daita, for instance, shows an incredible sensitivity for proportions in the articulation of the different interior spaces. It is in that house that I understood the concept of ‘relative proportions. Although my own work might be characterized by pure shapes and spaces, it also deals with the meaning of proportions in a particular situation and is less concerned with absolute values.

I would say the purpose of my PhD was less about completing the degree and more about better understanding my own work and clarifying my approach, especially toward proportions in architecture. In the tradition of Shinohara, proportions relate to an idealistic understanding of beauty driven by a given system of proportions. Elementary geometry or symmetry is almost its precondition. My goal however was to put the viewer and its body perception at the core of my investigation, understanding proportions less as absolutes than as a system of relations. This shift can be retraced in a series of buildings from the 1990s, which I investigated by studying the relations between different room sizes, between different floor heights, and between different building elements. This understanding of proportions as a set of relations has real potential. In my house Pilotis in a Forest, for instance, the height of the stilts is crucial. If they were a bit lower, the house would have become too architectural. If they were a bit higher, it would have become a tree house in the forest. This search for the possibilities of relative proportions, depending on the surroundings, is a fundamental topic of both my research and my practice.

Accordingly the elements of architecture seem to play a crucial role in your buildings. You often refer to them as key to the whole project: the ‘pilotis’ for the house in the forest, the ‘balcony’ for the Nerima Apartments, and the ‘windows’ for the Rowhouse in Ageo.

Everybody knows what a roof or a balcony is, and this evidence allows me to discuss a project easily with non-architects. But this evidence goes beyond the everyday communication. Elements allow also to interact with the surroundings, and that’s what I’m looking for when designing: What is at stake is similarity, rather than identity.

In an essay on the Japanese roof, you argued for a Japanese archetype, in which the roof has a dominant shape, whereas the walls are considered secondary elements. Are these elements part of a more profound or even historical paradigm? Are you looking for archetypes and prototypes at the same time?

I think both. The possibilities and combinations of architectural elements are unlimited. In every building you can enjoy them anew. But as I mentioned, the local language of the site plays an important role in my design. My first building in Karuizawa, the House in a Forest, has a steep roof, as all the other buildings have. The House in Kamae reinterprets the front garden so common in the neighborhood. And the Townhouse in Asakusa plays with the theme of the balcony. But at the same time, I am always concerned with a universal statement. Therefore, there is no contradiction for me between the general and the specific. I look for the general in every particular project.

And how do you translate it in your practice?

The best way to describe it would probably be the notion of proportion, which deals both with form and environment, with questions of space and size and their relation to the body, but also with a specific location, with its specific topography, climate, time, etc. I am convinced of the necessity to engage in a specific way with the specific context of a commission. The client determines the singularity of every project. Even if many architect are not concerned with these issues, I see this as an opportunity to fight against a homogenization of our build environment. Everybody lives in a different way, shaping different spaces. Hence, I want to see how my clients live, what kind of objects they own, how they behave at home, if and how they clean their house. That’s where my proposal starts. In fact, when designing a project, I use to meet with clients in their houses, even if it means carrying huge models with me.

For instance, in the House in Sangenjaya, the clients, who work all the time, wanted to have an outdoor space like a garden in which to relax for a few hours on Sundays. This condition became the driving force of the project. In the neighborhood, a very dense urban area near Shibuya, I discovered that every house and apartment has a very small balcony. I just inverted the proportions between house and balcony: on its top floor, the house is now only 1.1 meters wide but has a large, 2.6-meter-wide concave balcony. Similarly, on the first floor, the clients needed a very large covered parking space for their jeep. We consequently provided a corresponding entrance drive with a concave shape, allowing some light to enter the bedrooms on the basement floor.