The Details of Modern Architecture

Ford, Edward R. (1990 & 1996). The Details of Modern Architecture, Vols.

1 & 2. The MIT Press.

金贝尔博物馆是路易斯康最优秀的建筑之一,可能是因为它打破了康自己的许多规则。这并没有严格定义的结构元素(“房间” ),结构秩序和空间秩序之间没有直接的联系,室内外之间也没有中间空间。墙壁不是整体的,也不像整体。

这座两层楼的建筑建在一座山上,所以它的后面只有一层楼高,面对着一个公园。上层的屋顶结构由混凝土拱顶组成,短边尺寸相对较窄,但长边尺寸跨度超过100英尺。有两个内部庭院打断了拱顶,每个拱顶顶部都有一个狭缝,允许光线进入内部,还有面向公园的窗户。

混凝土拱顶截面为摆线,由滚动圆上的一点形成。这种形状是美学上的选择,而不是结构上的选择,而且这种形状在建筑史上几乎没有先例,尽管埃德温·鲁琴斯(Edwin Lutyens)在他的拱桥(比如汉普顿宫Hampton Court的那座拱桥)上使用了相当扁平的形状。

拱顶的长跨度是通过后张预应力钢筋混凝土实现的,后张钢筋沿着拱顶的长向呈长长的大弧线。路易斯康对Komendant的第一张设计图的回应是,就像大多数建筑师会做的那样,边缘梁看起来太小了,不足以支撑这么长的拱顶。 Komendant 的回应是康的看法是正确的:是拱顶承载着梁,而不是梁承载着拱顶。

下面的地板,虽然是平的,也是后张预应力,尽管较小的跨度。在这里,康使用了类似华夫饼的结构,但在顶部和底部都有混凝土平板。因此,内部的模板不能被拆除,而是由泡沫块制成留在结构内的。

在罗切斯特唯一神教派教堂 、 埃克塞特图书馆 和 萨尔克生物研究所 ,建筑秩序与房间的规划紧密匹配。因此,埃克塞特的有自己独特的结构和空间。在金贝儿结构是主导,与展览空间几乎没有或根本没有共同点,房间被放置在一个为此目的而设计的结构系统中。图书馆和礼堂被挤进了由摆线拱顶创造的狭长的空间。结果并不令人不快,但可以说是不合适的,特别是在礼堂,凹拱顶集中而不是分散的声音。

虽然路易斯康喜欢这句古老的格言“节点是装饰的开始”,但他在金贝尔的使用比在其他地方少。一些关节以相当难以捉摸的方式隐藏起来,无论是出于经济上的需要,还是出于一种普遍的克制感。他选择了平缝铅顶,而不是当时流行的立缝铜顶。一个更有趣的细节出现在预应力棒末端的帽。在他们的原始形式这些末端是难看的,并需要覆盖以防止生锈。这个问题的一个典型解决方案是放置一个铬帽在杆端“装饰”连接处,这在20世纪60年代的建筑中是一个常见的细节。节点大量出现在金贝尔,特别是在柱顶和拱顶。康曾想用大理石板覆盖这些,但预算不允许这样做,端头设置在空腔里,然后用混凝土填满。从近处看,细节显得有些粗糙。

金贝尔像大多数博物馆一样,拥有大量的参观者和大量的灯,因此需要频繁的换气,因此需要大量的管道系统。金贝尔的公共部分本质上是一个单层建筑,空气可以像在罗切斯特教堂那样分布在楼板上,但卡恩选择了一个更紧密的集成系统,将管道放置在画廊的结构中。没有像 理查德医学院 那样暴露的管道系统,也没有像 萨尔克生物研究所 那样用混凝土包裹的管道。金贝尔的每个拱顶之间都是浅u型混凝土通道,从中悬挂着一系列线性金属盘,空间创造了两个供气管道,一个用于通道两侧的画廊。中央机械房位于地下,管道通过长向之间的小跨度到达屋顶结构。混凝土U盘和金属盘之间的线性扩散器分布空气,同时充当支撑隔板顶部的支架。回风是通过一些内部分区底部的槽来完成的,这些槽通向地下室的竖井。从画廊空间看,这个系统看起来很简单,但是需要对混凝土结构进行大量的修改,以支持缝隙上方的墙壁。这是路易斯康希望在暴露结构的同时集成公共设施的一个较好的解决方案。管道系统是隐蔽的,不需要特殊的工艺。公用空间很容易通过金属天花板进入,允许以后对系统进行调整和修改。新风扩散器和回风格栅,由于不显眼,不与视觉上的艺术竞争的注意。但是,这个解决方案对手头的问题来说有些独特,路易斯康没有再使用它。

虽然结构在路易斯康的作品中是不典型的,但结构与非结构元素之间的关系却并非如此。在建筑的短端,石灰华和混凝土块幕墙与混凝土拱顶相遇的地方,一个微小的锥形槽将两者分开。洞口布满了无框有机玻璃。卡恩写道:石灰华和混凝土完美地结合在一起,因为无论浇注过程中出现什么违规或误差,都必须会呈现出来。

石灰华非常像混凝土——它的特征是它们看起来像相同的材料。这使得整个建筑再次成为一个整体,没有分离。主层的非承重墙在外部是石灰华,有时在内部也是。事实上,它们是混凝土砌块墙,表面有1英寸的石灰华。这些细节的处理方式并没有什么不雅之处,但它们给路易斯康带来了一个他不喜欢的问题,那就是贴面。为了避免在砖木或石头上使用贴面,他走了极端。他在 埃克塞特图书馆 Exeter Library 的隔间上坚持使用实心橡木嵌板,只是最极端的例子。路易斯康在金贝尔的问题是,鉴于现代石材建筑技术,某种类型的贴面几乎是不可避免的,整体石墙石灰华是根本不可能的。当然,他以前也遇到过这个问题,尤其是在布林莫尔宿舍楼的L楼,以及索尔克研究所的早期研究中。在金贝尔会议上,他提出了一个与他成熟风格不同的解决方案。墙的混凝土暴露在墙面和地面,试图表明这些石头只是表皮,这可能是一个尴尬的细节,因为它需要精确的材料,石头和粗糙的,有时不准确的混凝土的连接。

里有很多其他的贴面材料,但所有的材料都很详细,以显示它们是贴面材料。内部独立的隔墙覆盖了木材和织物,但有金属端部,以显示表面的薄。石灰华墙更加模糊。两端没有暴露,甚至没有显露出来,连接方式类似于传统石墙。可以说,这与索尔克式的细节没有什么不同,但不能说金贝尔式的细节与路易斯康的其他作品是一致的。

就像非承重隔墙一样,窗户与包含它们的结构清晰地分开。深层的展示将窗户与周围的混凝土相映衬,使窗户看起来漂浮在开口中,再一次,展示被用来连接光滑精确的材料和粗糙粗糙的混凝土,同时保持体量的几何纯度。卡恩再一次使用了内釉面不锈钢系统(这里用胶合板加固)来实现一个紧绷的精确膜,其张力只有在竖框上的图案被打破。再一次,窗户是用框架和现场制作的,在展示处用拼接连接,而不是更常见的木棍系统。令人惊讶的是,很少有钢框架与石灰华墙连接。所有的大窗户都在混凝土结构的开口中,石墙从未被开口穿孔或穿透。唯一的玻璃和石头的连接处出现在没有使用框架的墙壁顶部的小开口处。

然而,金贝儿最引人注目的地方不是窗户,而是天窗。它们的面积要比窗户小得多,窗户是每个拱顶上的一条窄条,但它们的效果要显著得多,尤其是在部分多云的日子里,当阴影穿过博物馆的地板时。卡恩曾希望用这个插槽来照亮画作,但事实证明这是不可能的,具有讽刺意味的是,这种光线从未到达画作,而是被一个穿孔的金属扩散器偏转,并被扔到拱顶上,以避免不受控制的阳光可能对画作造成的损害。

帕特丽夏·朗(Patricia Loud)指出,尽管人们对金贝儿美术馆的反应过去是、现在仍然是热烈的,但有几位批评者对金贝儿的结构合理性提出了质疑。有趣的是, 六十年前埃利尔·沙里宁被批评为同样的原因。路易斯康采取了属于砖石拱顶,却用混凝土浇筑,虽然结果不是不合适,也不是富有表现力的材料或过程。该建筑的巨大成功在于它引入了自然光,尽管自然光在完工的建筑中受到了减弱,但这是他的下一个也是最后一个建筑(耶鲁大学英国艺术中心)所关注的问题。

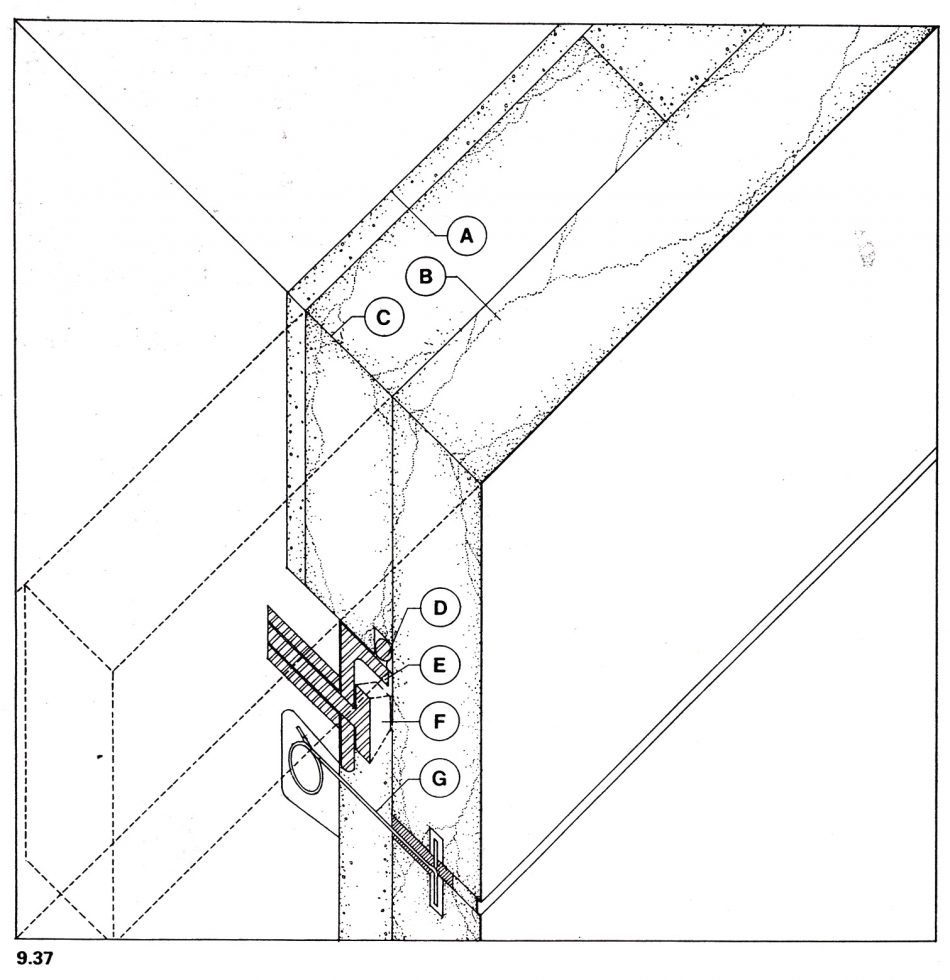

石材细部构造

A

Bocked-out area of concrete wall to receive anchor

B

1+1/4 travertine panel

C

4 X 8 X 1+1/4 support panel epoxied to rear of travertine to transfer the weight of the panel to the steel clip

D

Bead welded to angle to prevent lateral movement of the stone

E

Support cut from 2×1/4×10″ long steel angle to take the weight of the stone panel to the concrete wall

F

Expansion bolt anchoring clip to concrete wall

G

Wire anchor to laterally support the top of the stone panel below

墙身与屋顶构造细部构造

窗户细部构造

The Kimbell Museum is one of Kahn’s finest buildings, in spite or perhaps because of the fact that it breaks so many of his own rules. There are none of the tightly defined structural elements that Kahn defined as”rooms “, there is no direct correlation between the structural order and the spatial order, and there are no intermediate spaces between interior and exterior. The walls are not monolithic and do not appear to be monolithic.

The two-story building is set on a hill so that it is one story tall at the rear, which faces a park. The roof structure of the upper floor is composed of concrete vaults, relatively narrow in their short dimension but spanning over 100 feet in their long dimension. There are two interior courts which interrupt the vaults, a slit in the top of each vault to allow light into the interior, and windows facing the park.

The concrete vaults are cycloids in section, the shape generated by a point on a rolling circle. This shape was an aesthetic choice rather than a structural one, and the shape has few precedents in architectural history, although Edwin Lutyens used it in rather flattened form in his arched bridges, such as the one at Hampton Court.

The vaults achieve their long spans by means of post-tensioning rods that run in long sweeping curves along their lengths. Kahn responded to Komendant’s first drawing of the design by saying, as most architects would, that the edge beams seemed too small to carry the vault over such a long span. Komendant’s response was that Kahn’s perception was correct; it is the vaults that carry the beams, not the beams that carry the vaults.

The floor below, although flat, is also post-tensioned despite the smaller bay size. Here Kahn used something similar to a waffle slab but with flat slabs of concrete at both top and bottom. The formwork of the coffers could thus not be removed and was made from foam blocks that remained within the structure.

At Rochester, Exeter, and Salk, the structural order is tightly matched to the program of rooms. Thus the card catalogue at Exeter has its own particular structure and its own particular space. At the Kimbell the structure is dominant; rooms that have little or nothing in common with exhibition spaces are placed within a structural system designed for that purpose. The library and auditorium are shoehorned into the long narrow spaces created by the cycloid vaults. The results are not unpleasant, but are arguably inappropriate, particularly in the auditorium where the concave vaults focus rather than diffuse the sound as is desirable.

While Kahn was fond of the old adage”the joint is the beginning of ornament” he made less use of it at the Kimbell than elsewhere. a number of joints are concealed some in rather elusive ways, whether through economic necessity or a general sense of restraint. He chose a flat-seam lead roof rather than the standing-seam copper popular at the time. A more curious detail occurs at the caps at the end of the prestressing rods. In their raw form these ends are unsightly, and in any case need to be covered to prevent rust. A typical solution to this problem was to place typical solution to this problem was to place a chrome cap over the rod ends”ornamenting” the joint, a common detail in buildings of the 1960s. The condition of rod ends occurs frequently at the Kimbell notably at the tops of columns and at the ends of the vault. Kahn had wanted cover these with marble plates, but the budget, which was by no means generous would not allow this, and the end strands were set in pockets later filled with concrete. Viewed from close up the detail appears somewhat crude.

The Kimbell, like most museums, has a large number of occupants and a large quantity of incandescent lighting and thus requires frequent air changes and hence a large quantity of ductwork. The public parts of the Kimbell are essentially a one-story building and the air could conceivably have been distributed through the floor slab as it was at the rochester church, but Kahn chose a more tightly integrated system, placing the ducts within the structure of the gallery. There is no exposed ductwork as there is at Richards and there are no ducts encased in concrete as at Salk. Between each vault at the Kimbell are shallow U-shaped concrete channels from which are suspended a series of linear metal pans The space created holds two supply air ducts one for the gallery on each side of the channel. The central mechanical room is on the floor below and the ducts reach the roof structure through the small bays between the long spans. a linear diffuser between the concrete U and metal pans distributes the air, as well as serving as a bracket to brace the tops of partitions. Return air is accomplished by slots at the bottom of some interior partitions which lead to shafts in the basement. This system appears simple when seen from the gallery space, but requires considerable modifications to the concrete structure in order to support the wall above the slot This is one of the happier solutions to Kahn’s desire to integrate the utilities while exposing the structure. The ductwork being concealed, requires no special crafts-manship. The utility space is easily accessible through the metal ceiling, and allows for later adjustments and modifications to the system. The supply diffuser and return air grilles, being unobtrusive do not visually compete with the art for attention. But again this solution was somewhat unique to the problem at hand and Kahn did not use it again.

Although the structure is atypical of Kahn’s work, the relationship of structural to nonstructural elements is not. Throughout the building the infill elements are held back from the vault and columns with reveals and windows The reveals serve a functional purpose where precision finish materials must join with relatively crude concrete, but they and the windows serve chiefly to clarify what is supporting the vault and what is not. Thus at the short end of the building, where the travertine and concrete block curtain wall meets the concrete vault, a tiny tapered slot separates the two. The opening is filled with frameless Plexiglas. Kahn wrote: “Travertine and concrete belong beautifully together because concrete must be taken for whatever irregularities or accidents in the pouring reveal themselves.

Travertine is very much like concrete-its character is such that they look like the same material. That makes the whole building again monolithic and doesn’t separateings. The non-bearing walls on the main floor are travertine on the exterior and sometimes on the interior as well. In fact they are concrete block walls faced with 1-inch travertine. There is nothing inelegant about the way in which they are detailed, but they presented Kahn with a problem with which he was uncomfortable that of veneering. He went to great extremes to avoid the use of veneers whether in brick wood,or stone. His insistence on solid oak panels in the carrels at Exeter is only the most extreme example. Kahns problem at the Kimbell was that, given the technology of modern stone construction, some type of veneering was almost inevitable Monolithic stone walls in travertine were simply out of the question. Of course he had faced this problem before, particularly at the af of L Building the bryn Mawr dormitory, and the early studies for the Salk Institute. At the Kimbell he developed a solution that was somewhat atypical of his mature style. The concrete is exposed on the face of the wall at the edge and at floor levels, attempting to make it clear that the stone is only a facing This could be an awkward detail, since it requires the joining of a precision material, stone with a crude and sometimes inaccurate one, concrete, but this type of juxtaposition is common in Kahns work as a whole.

The Kimbell is filled with many other materials that are veneered, but all are detailed in a way to show that they are veneers. The interior freestanding partitions are clad in wood and fabric but have metal ends to show the thinness of the surface.The travertine walls are more ambiguous. The ends are not exposed or even revealed, and the joint pattern resembles that of a traditional stone wall. It could be argued that this is not dissimilar to the Salk-type detail, but it cannot be argued that the Kimbell detail is consistent with Kahn’s other work.

Like the non-bearing partitions, the windows are clearly separated from the struc- ture that contains them. a deep reveal sets off the window from the surrounding concrete so that the windows seem to float in the openings, and once again the reveal is used to join a smooth precision material with a crude and rough one concrete, while preserving the geometric purity of the volume. Once again Kahn uses an inside-glazed stainless steel system (here reinforced with plywood )to achieve a taut precise membrane whose tension is broken only by the pattern of reveals at the mullions. Once again the windows are shop-fabricated in frames and field- joined at the reveal with a splice instead of the more common stick system. It is surprising to note how rarely a steel frame joins with a travertine wall. All of the large windows are in structural openings in the concrete the stone walls are never punched or penetrated by openings. The only junctions of glass and stone occur at the small reveals at the tops of walls where no frames are used. The most remarkable aspect of the Kimbell, however is not the windows but the skylights. They are much less extensive in area than the windows a narrow strip at the top of each vault but they are much more dramatic in effect particularly on partly cloudy days when shadows travel across the floor of the museum. Kahn had hoped to use this slot to light the paintings, but this proved impossible, and the irony is that this light never reaches the paintings, being deflected by a perforated metal diffuser and thrown onto the vault to avoid damage to the paintings that uncontrolled sunlight could cause.

Patricia Loud has pointed out that while response to the Kimbell was and remains enthusiastic, several critics have questioned the structural appropriateness of the vaults. Kahn, interestingly enough, was criticized for the same reasons as eliel Saarinen had been sixty years earlier, that he had taken a form inherent to masonry the vault, and executed it in concrete, and while the result was not inappropriate, neither was it expressive of the material or the process.The great success of the building was in its introduction of natural light, however compromised in the finished building, and it was a concern that was to dominate his next, and last building.

区分、消隐与对位——形式与建构思想下路易斯·康的节点秩序表达

卢峰, & 刘宇. (2016). 区分、消隐与对位——形式与建构思想下路易斯·康的节点秩序表达. 西部人居环境学刊,31(4), 58-62.

节点区分脱离

将填充墙与梁脱开0.324m,并嵌入玻璃,揭示了墙体非承重的特质,同时形成了弧形采光带。

节点装饰性区分

在美术馆的山墙面,由于空腔墙体的存在,室内楼板与墙体是脱开的,而康却仍在山墙对应的位置虚设了装饰性的“结构带”,来达到分层的视觉效果,这样的做法从山墙延伸到了正立面。这说明节点区分对于康来说,更像是一种建造程序及建构的几何秩序姿态的表演,而非忠实地呈现结构理性。